Guest Essay written by Spouzhmai Akberzai, member of the Afghan Women’s Network

For decades, Western interests have securitized and de-securitized the security, rights, and agency of Afghan women.

The climate created by the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and UN Security Council Resolution 1325 in 2000 influenced Afghanistan’s 2004 Constitution and the National Action Plan on Women in Afghanistan. These policies were instrumental for Afghan feminist activists in civil society, the government, and academia to advocate for gender-inclusive peace and security policies at the national level. The paradigm shifts from political realism and traditional security to non-traditional and human security places Afghan women at the heart of the peace process in Afghanistan—except it has failed to secure women’s agency and meaningful participation.

In 2001, in an act of retribution to the attacks on 9/11, the United States declared a “War on Terror” in Afghanistan. The Bush administration called upon the world to either stand with a “failed state” that harbors terrorism, or eliminate Al-Qaeda. First Lady Laura Bush urged the world to condemn the oppression of Afghan women in a radio broadcast.

I believe the politicization of women was meticulously used as a tool to justify Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan. Women’s security was embedded into the foreign policy agenda of United States, Canada, Sweden, and European countries, including the United Kingdom. This came at a time when the U.S. had not even signed the CEDAW and grappled with its own credibility related to human rights abuses. I feel that Afghan women were being used as a ventriloquist’s dummy to justify the invasion of Afghanistan.

This ventriloquism of Afghan women continued through 2018. However, despite the unprecedented insecurity, Afghan women continued to modify donor-prescribed developments imported from the international community. The Afghan women’s feminist perspective of security was broadened beyond realpolitik to a human security paradigm. Women’s rights were broadly institutionalized; quotas, reservations and systemic reforms took place throughout these years.

As a result, numerous reforms were introduced and welcomed by Afghan women; their political rights and 27 percent representation were guaranteed in the Constitution of Afghanistan. The country had signed certain international treaties and conventions to secure women’s equal rights. For instance, the ratification of CEDAW and CSW secured women’s political rights through affirmative action. The Elimination of Violence Against Women (EVAW) was a milestone legislation towards better protecting the rights of women’s security in Afghanistan when it was passed as a presidential decree in 2009. The law meant to criminalize acts of violence against women, including rape and domestic violence, child marriage, forced marriage, the exchange of women in blood feuds, and other disputes (a practice known as ‘baad’ which is prevalent in Afghanistan), among other forms of violent acts against women.

Additionally, prominent gains came from women parliamentarians bargaining on the Child Protection Act. Women and child activists hailed the win as a landmark development, criminalizing under-age marriages. Female participants using UN Security Council Resolution 1325 were at the forefront of its passage through the Lower House of Afghanistan’s Parliament. Women were also participating in nation building and peacemaking initiatives. Nine out of 79 members involved in negotiations with the Taliban on the High Peace Council were women.

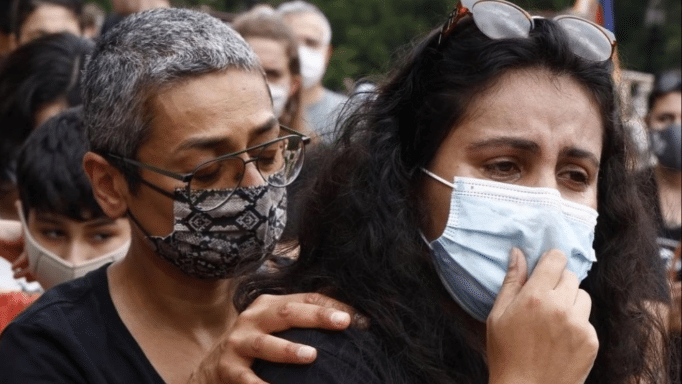

While the human security of women during peace building was prioritized and politicized for the last 20 years, the U.S. unpredictably de-securitized women in a turbulent peace deal signed with the Taliban in Doha. Women were no longer a significant factor in U.S. foreign policy in Afghanistan. The symbolic use of Afghan women to justify a U.S. war came to an end when the U.S. decided to withdraw, leaving the fate of Afghan women at the mercy of a patriarchal society and a terrorist group in particular. Their agency, however symbolic, was de-securitized during the “so-called” peace deal signed between the Taliban and the United States in February 2020. From a supposedly women-centric foreign policy in 2001 to the politics of reductionism in 2020, women’s security plunged from panic politics to normal politics.

Afghan women’s exclusion from the peace deal had been the first risk factor for women’s uncertainty followed by their symbolic presence on the negotiation table with the Taliban during intra-Afghan talks in Doha. In an interview with Habiba Sarabi, the first female governor of Afghanistan, who was also a member of the intra- Afghan peace talks delegation, Sarabi said:

“Taliban would not talk to women. Each time I asked them to include a woman in their team, they said why don’t you represent us? They ambiguously interpreted women’s rights as rights designated to women under Sharia. A much (sic) of secrecy was going in the intra-Afghan peace negotiations.”

The epistemic violence of the U.S. and the international community in leaving women out of the peace process represents a colonial feminist logic. The champions of women interests, and representation backtracked on 20 years of ideals in regard to democracy, human rights, liberties, achievements, and reforms by signing an agreement with the Islamic Emirates of Taliban, a terrorist group perceived to be the enemy of ideals stated above. A masculine war followed by masculine peace once again decided the fate of Afghan women.

The entire 20 years of tension between women’s security over militarism has, in fact, resulted in a retreat of women’s social and political ideals to the dark days of women’s social existential threat and an atmosphere of uncertainty. What Afghanistan is experiencing today is a more diplomatic terrorist group where representatives of the Taliban have masked their atrocities and war crimes undertaken post August 2021. By not allowing women to go to secondary school, limiting their employment and movement, and controlling their dress they are, once again asserting their control over women—a phenomenon we are seeing throughout the world.

###

All views expressed by the author are her own personal views and not of Vital Voices Global Partnership.

About the Author:

Spouzhmai Akberzai is an intersectional feminist and member of the Afghan Women’s Network. She holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in Political Science from the University of Delhi. She is a former fellow on Youth Atrocity Prevention – Feminist understanding of Violence in International Coalition of Sites of Conscience (ICSC) and currently pursuing a fellowship on Every Women’s Treaty, a global campaign for an international treaty to end all forms of violence against women and girls.